Science at work 14 January 2026

- Home

- CIRAD news

- News

- Combating imported deforestation in the EU

The European Union and imported deforestation: research has a vital role to play

© Pixabay

The essentials

- The EU Deforestation and Forest Degradation Regulation (EUDR) is due to come into force in 2026. It will put a stop to imports of products that contribute to deforestation in seven agricultural value chains.

- To be effective, the regulation will have to allow for the diversity of forest ecosystems. In view of the vast task ahead, research will have to come up with operational indicators capable of differentiating between preserved and degraded forests.

- Millions of small family farms will be affected. Little is yet known about the impacts on how value chains are organized.

The regulation includes an eventual total ban on exports to the EU of products that have contributed to deforestation post-2020. Cocoa, coffee, palm oil, soybean, rubber, beef and wood are the value chains currently concerned, but the regulation should subsequently be extended to other agricultural products. Similarly, while forests are the first target ecosystems, peatlands, grasslands and wetlands should be included in the new regulation in future. In addition to imports, production within the EU is also subject to the regulation, so French Guiana, which is 90% forest, is therefore concerned.

The aim is both clear and ecologically responsible, but unfortunately, the task ahead is more complex than anticipated. To define the concepts of deforestation and degradation, the current regulation relies on a single definition of what constitutes fort, based on fixed structural parameters in terms of vegetation. The snag is that in reality, the diversity of the world's forest ecosystems rules out the adoption of a single definition of "non-degraded forests" that could serve as a reference to identify non-disrupted forests. Furthermore, the regulation obliges producers to geo-locate their products precisely, but the technology required is often inaccessible to the millions of small-scale farms in the global South.

As well as negotiating technical challenges and political choices, the relation will not just have to address ecological issues but to adapt to the economic and social constraints facing the range of stakeholders in the agricultural value chains concerned. Research must therefore play an active part in finding reliable indicators and be able to suggest viable adaptations for family farmers in the global South, who sometimes rely on exports to Europe for a living.

Identifying degraded zones is harder than it looks

The EU has opted for the FAO definition in choosing the zones concerned by the regulation. "For FAO, a forest is an area with at least 10% tree cover across half a hectare", says Lilian Blanc, a forest ecologist with CIRAD. "The trees have to be at least five metres tall. There are therefore two criteria - forest cover and tree height - that can theoretically be used as a baseline. Zones that fitted the criteria in 2020 but no longer do are considered as degraded. Products from such zones can no longer be imported into the EU."

The problem is that the above definition does not work for some biomes. According to the researcher, some natural forests are much denser, for instance, so the FAO definition corresponds to a degraded version of their natural state: "If we simply apply the FAO criteria, we sometimes end up confusing degraded forests and natural ecosystems". To make matters even more complex, some cases of degradation are in fact seen as the opposite, with the introduction of invasive exotic species that boost forest cover or tree height while local species disappear below the new trees.

Defining specific reference indices for every biome

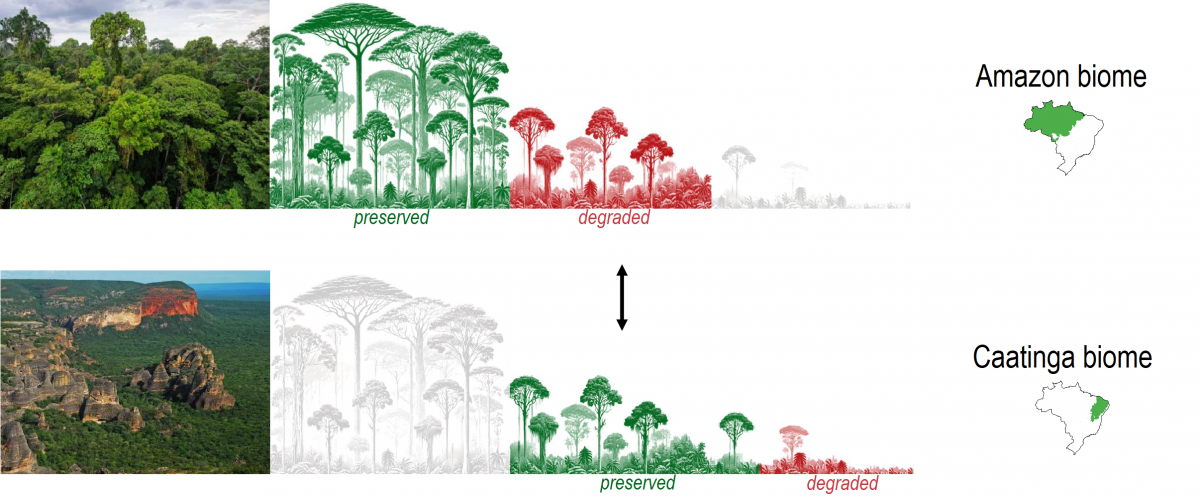

CIRAD led a study by a consortium associating scientists from the CNRS, IRD, CIFOR and ECOFOR on behalf of the Comité scientifique et technique Forêt (CST Forêt). Camila Rezende, a CIRAD post-doc student, suggests a new method to set a "preserved forest" reference for each of the major biomes. Taking two major biomes in Brazil as an example, it is clear that what would be classed as the "preserved" situation for the Caatinga forest corresponds to a "degraded" situation for the Amazon forest. Differentiating the two ecosystems makes the indicators more realistic.

"A given vegetation height and tree cover standard may therefore be seen as highly degraded in the Amazon rainforests, but correspond to preserved dry forests in Caatinga", Camila Rezende explains. In October 2024, the consortium presented its first forest classification results. The aim of this work is to provide the EU with reliable, effective indicators for identifying "green zones" and "red zones" in each major forest biome. The consortium is also working to find easily applicable measurement and monitoring methods that could also be used in countries other than Brazil.

Anticipating the EUDR's impact on small-scale producers, to give them more effective support

In addition to the technical questions surrounding forest classification, the regulation raises another issue: the possible exclusion from the EU market of millions of family farms. To function correctly, the regulation relies on product traceability. Producers therefore need to be able to geo-locate their farm precisely, as must processors, to guarantee the traceability of any raw materials that may be mixed together. The trouble is that for many farmers in the global South, notably those most isolated, geo-location technology is not as accessible as it is in the North. For instance, in West Africa, it is estimated that only 20% of people have smartphones.

For CIRAD, which has been working with the above partners for decades, this is a crucial issue. Family farms are in the majority in many tropical and Mediterranean countries, and some value chains, such as cocoa, rubber and coffee, are particularly concerned, with small, often isolated farms covering just one or two hectares. In a year's time, those families will have to be able to provide the EU with this information. It is unclear how they will go about it.

The new regulation will therefore almost certainly mean a reorganization of some value chains. CIRAD, like its partners, will have to act as an observer, to document the changes for and impacts on millions of family farms across the world. However, research could also steer the regulation towards alternatives in terms of certification, for solutions that would be more accessible to small-scale producers yet remain both reliable and traceable. CIRAD and its partners in the global South are looking into participatory certification schemes such as participatory guarantee systems in particular.

The EU Deforestation and Forest Degradation Regulation is vital for protecting the world's forests. It requires a global debate not just on how we see forest ecosystems, but also on the support the EU gives to producers in the global South. One thing is certain: to be effective, the drive to combat deforestation must also encompass economic and social aspects.