Call to action 25 November 2025

- Home

- CIRAD news

- News

- The energy transition and the mineral rush

The mineral rush: the hidden cost of the energy transition

Construction d'une mine au Suriname © ILC

In the European Union alone, where the Commission is aiming for carbon neutrality by 2050, the demand for minerals required for the energy transition is projected to rise between 1.5 and 7 times by 2030. These International Energy Agency figures illustrate a global trend that is driving the mining sector to seek new lands for extraction.

However, “lots of mines are being opened in areas that are facing land and food insecurities”, says Jérémy Bourgoin, a geographer at CIRAD and at the International Land Coalition (ILC). The scientist has just co-published a new article in World Development Perspectives that reviews the current state of the international mining network through land acquisitions.

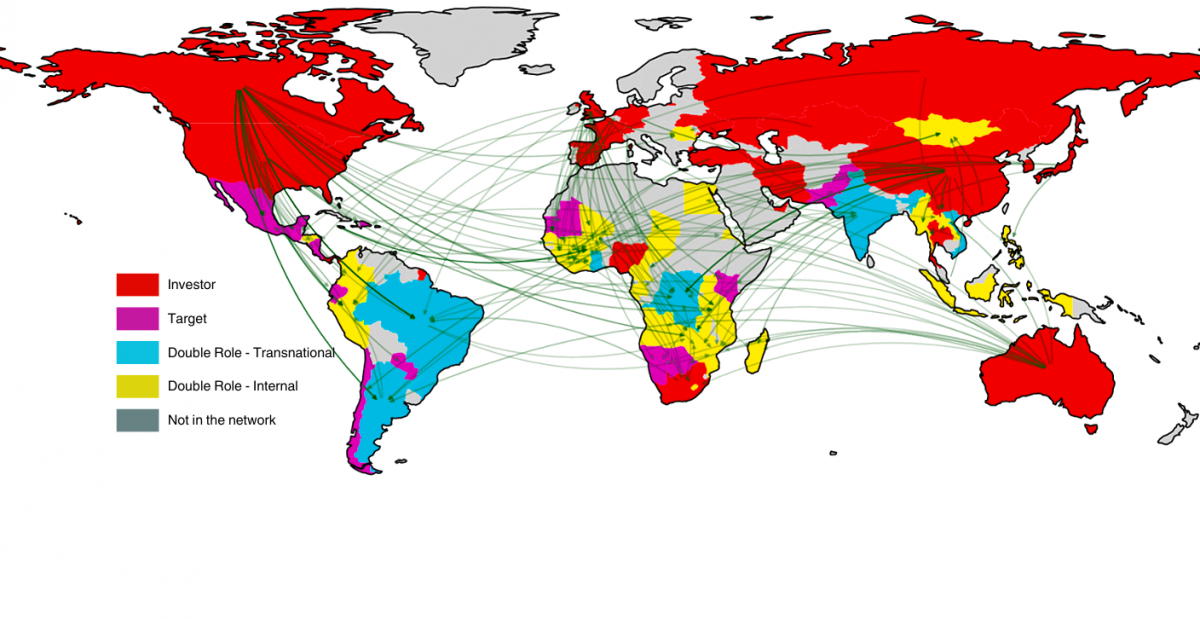

The findings reveal that the majority of investors come from countries of the “North”, including Canada, the United States, Russia, China and the European Union. Most land acquisitions, on the other hand, are located in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia. All of this publicly available data has been compiled by the Land Matrix Initiative, which documents large-scale land investments throughout the world.

Deforestation, the exclusion of local populations and, arable land conversion for energy

In many cases, the lands acquired are already used for activities such as pastoralism, agriculture, gathering or hunting, which are essential to ensure food security for local people. Compounding this issue is the lack of consultation and exclusion of local communities, which result in disputes. The environmental costs are also significant: some mining investments are located in biodiversity-rich areas. Extractive activities often result in pollution of surrounding arable lands.

“According to all projections, global demand for minerals such as cobalt and nickel will continue to grow significantly”, says Jérémy Bourgoin. “The capacities for recycling these materials are still too limited. We therefore need to immediately start addressing the environmental and social impacts of new mines. The energy transition in some countries should not come at the expense of living conditions for people elsewhere in the world”.

“In this race for minerals, we often overlook the contexts in which these lands are acquired”, says Roberto Interdonato, a data scientist at CIRAD and co-author of the study. “Today, most conflicts surrounding large-scale land acquisitions are mining-related”.

Energy “transition” or energy “addition”?

Scientists are thus calling for a rethink of the dominant narrative on the energy transition: the materials needed for renewable energy technologies do not come from nowhere. “The current nature of land transactions means that land has become a financial asset, abstract and disconnected from its own geography”, says Jérémy Bourgoin. “The problem is that this masks the true costs of the transition”.

Considering the full range of impacts related to the energy transition could mean we need to rethink our societal model, according to Jérémy Bourgoin. “The term ‘transition’ itself is questionable, as what we have seen so far is more an addition of energy sources. Coal has not yet disappeared; we have just added oil, nuclear power, and so on. If we choose to pursue addition rather than substitution, we need to be aware of the costs”.

Reference

Jérémy Bourgoin, Roberto Interdonato, Quentin Grislain, Matteo Zignani, Sabrina Gaito. 2024. Mining resources, the inconvenient truth of the “ecological” transition. World Development Perspectives. Volume 35.