Expert view 5 March 2026

- Home

- CIRAD news

- News

- Combating animal trypanosomosis

Combating animal trypanosomosis in sub-Saharan Africa

Herd of cattle at a borehole © S. Taugourdeau, CIRAD

The essentials

- Animal trypanosomosis is a vector-borne disease caused by parasites transmitted to cattle by tsetse flies, and to a lesser extent by other blood-sucking insects. It remains a scourge for African livestock farmers.

- The COMBAT project focuses on lightening the burden of animal trypanosomosis in sub-Saharan Africa. It is based on progressive control pathways (PCPs), an evidence-based approach that is addressing grassroots realities in the hope of eradicating the disease.

- In view of the urgency, there is a substantial need for investment, tools and treatments. This requires massive long-term financial support from public- and private-sector donors.

Alain Boulangé, a molecular parasitologist at CIRAD, is COMBAT project coordinator. He is currently assigned to the Institut Pierre Richet in Bouaké, Ivory Coast.

The COMBAT project, funded by the EU and coordinated by CIRAD, associates 21 partners, including five European institutions, nine research organisations, six national veterinary authorities, and FAO. COMBAT, for "COntrolling and progressively Minimising the Burden of Animal Trypanosomosis", is helping to reduce and if possible eliminate the disease in the countries concerned. It is due to run for five years, in 13 African countries, and should contribute to alleviating poverty and eliminating hunger.

What are the main challenges and objectives relating to the fight against animal trypanosomosis?

Alain Boulangé: Trypanosomosis is one of the diseases that has the most serious repercussions for the cattle sector in Africa. It is a real scourge for African livestock farmers, who are powerless in the face of the impacts on their animals. The disease considerably restricts their financial resources, exacerbating poverty and hunger on the continent. There are no vaccines and the drugs that are available are becoming less effective as the parasites develop resistance. The aim of the COMBAT project is to boost the affected countries' capacity to control the disease. It relies on a One Health approach, which encompasses human and animal health and environmental protection.

We realised that there were gaps in terms of our knowledge of animal trypanosomosis, and more specifically of vectors, the parasite, hosts, and the interactions between them and with the environment. One of the major lines of research for COMBAT is to develop epidemiological research further in order to fill in the existing knowledge gaps. We are getting there, thanks to the interdisciplinarity between the partners involved. This enables close collaboration with local veterinary services, missions to provide training in diagnosis and vector identification, and missions to raise awareness of the disease among grassroots players, livestock farmers and decision makers.

We are also developing control tools to improve diagnosis and vector control, and building African livestock farmers' and veterinary services' capacity to combat the disease, while informing policymakers.

You have based your work on progressive control pathways (PCPs). What are they?

AB: One of the first things we observed was that not all the places affected by the disease are at the same stage in their fight against it. And it is therefore necessary to adapt control and combat strategies and harmonise them with the stage of disease development and its spread across a given zone. This is why we decided to use the PCP approach in building epidemiological information systems and national and regional strategies. The method hinges on organising actions in steps, with clearly defined stages, before moving on to the next stage, until the disease is eradicated. Those stages are not necessarily assessed on a national scale, but within specific zones of a country.

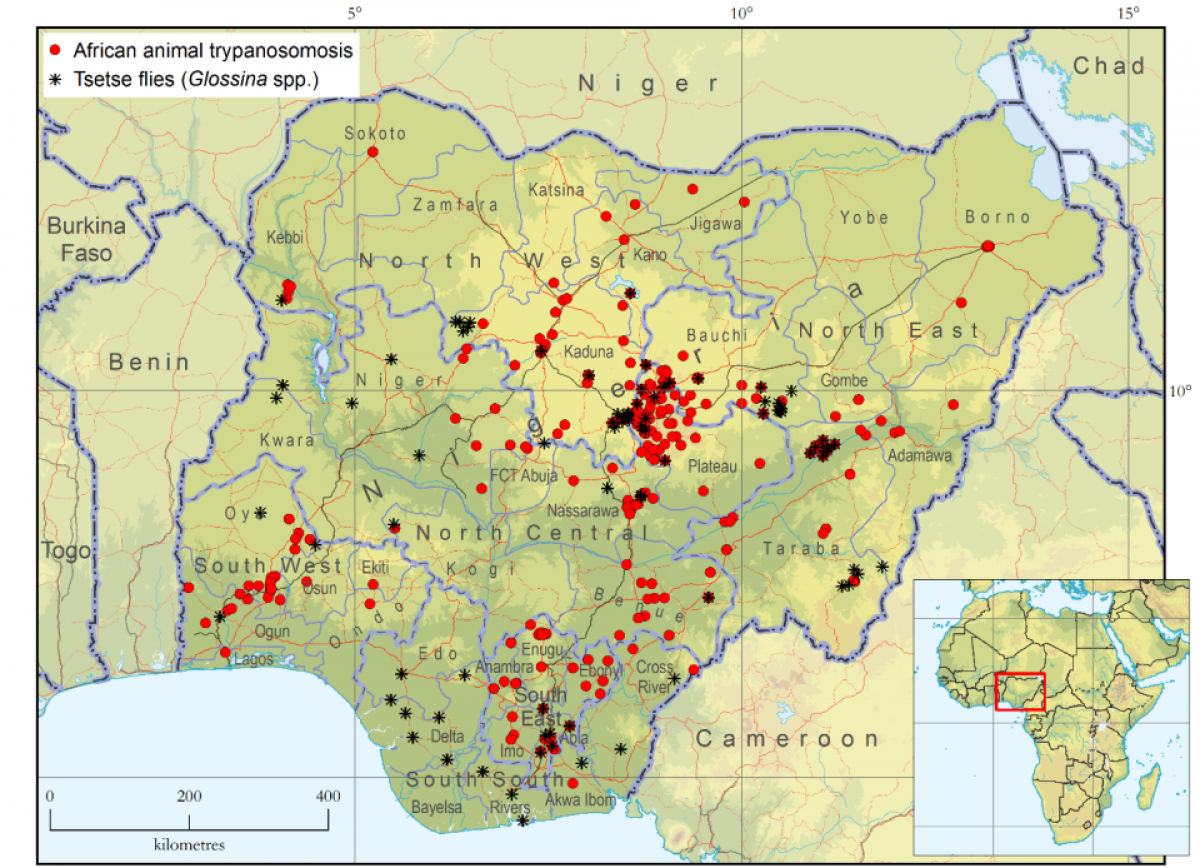

This approach is based on solid field evidence, acquired by means of a number of epidemiological tools. It allows us to compile atlases, in other words maps of where the vector and disease are found, to model the zones where control campaigns can be rolled out. We then do assessments to judge the success of the operation and decide whether the zone or country can move on to the next stage. This is done in line with the guidelines established based on the PCP and adopted by the countries' relevant ministries, which are then in charge of implementation. We therefore base ourselves on known data, with forecasts that can be made within a given time using the tools in question…

The PCP strategy was primarily developed by FAO, with the participation of CIRAD. It is not specific to trypanosomosis : the method has proved its worth for other cattle diseases in Africa, such as foot-and-mouth.

What progress has the project made and what are its prospects?

AB: As regards our knowledge of the disease, we can say we've achieved our overall aim, which was to help fill the gaps in our knowledge about both the disease and its vectors. A wide-ranging training programme has also been set up by and for the project members. The programme has targeted various players in the field, including laboratories, research centres, diagnostic centres, and veterinary services. To give just one example, the project has organised no fewer than seven two-week training workshops devoted to capturing and identifying blood-sucking flies, in the same number of countries. There have also been advocacy operations, including high-level seminars with government representatives from the affected countries, to make them more aware of the disease and the possible control approaches. Some of the countries in the consortium have gone so far as to draft roadmaps to coordinate control operations on a national and regional level.

We have also made significant progress in terms of control tools, notably with the development of improved screens to kill flies, which are more effective than the previous ones. These mini-screens, called "Tiny Targets" combine blue fabric to attract the flies with black mosquito netting impregnated with insecticide. They make use of the flies' vision-based behaviour, and significantly reduce population levels in an economical, ecofriendly targeted way. We have also developed traps suited to both tsetse flies and other blood-sucking flies, using biodegradable materials: "BioFlyTraps". The product satisfies current requirements and will have good commercial potential once the project is over.

As regards the development of diagnostic tools and drugs, we still need to adapt our methods, via co-construction workshops and using local resources, to meet grassroots requirements as far as possible.

We are pooling all our expertise and resources to help the communities affected by animal trypanosomosis manage better financially and boost the productivity of their agricultural and pastoral operations long term. This is a particularly long and costly undertaking, which requires major investments in terms of both time and funding.