Science at work 14 January 2026

- Home

- CIRAD news

- News

- Replanting palm groves in Indonesia

The renewal of palm plantations: a huge challenge for Indonesian agriculture

Small oil palm plantation on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia © Turinah

The essentials

- On the island of Sumatra, Indonesia, ageing oil palm plantations will shortly have to be replaced. Replanting is a critical time for smallholders, whose income will fall drastically for at least five years.

- There are also huge challenges in terms of soil and ecosystem preservation in new plantings, and several plantations are switching to agroecology.

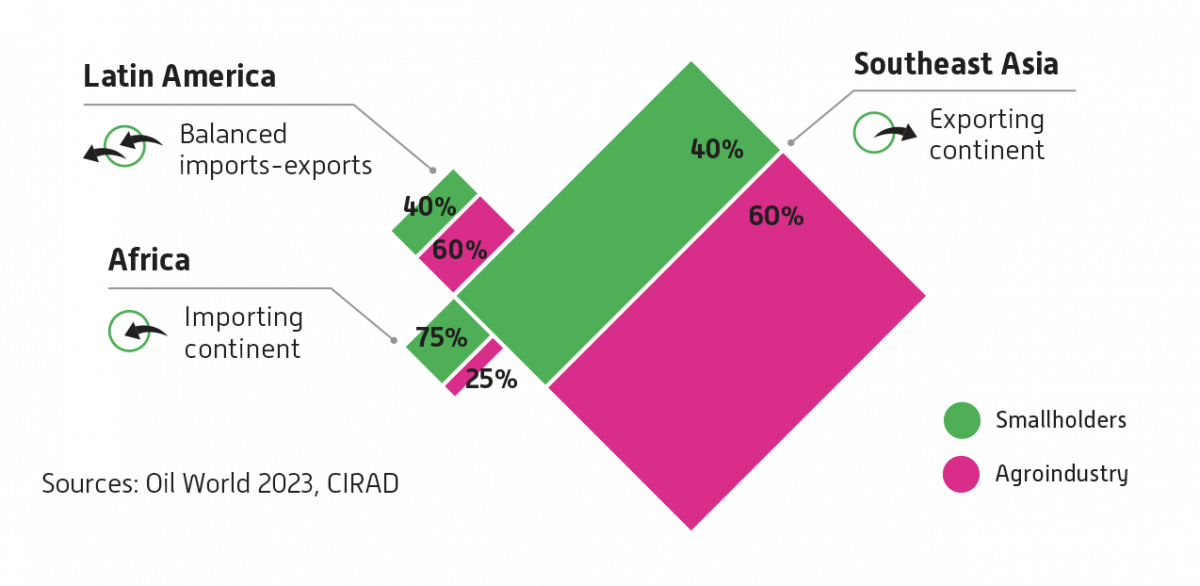

- In Southeast Asia, 40% of agricultural production comes from small-scale farms of around two hectares. In Indonesia, most family farms have slashed their pesticide use and are doing their utmost to respect European standards for sustainable oil palm cultivation.

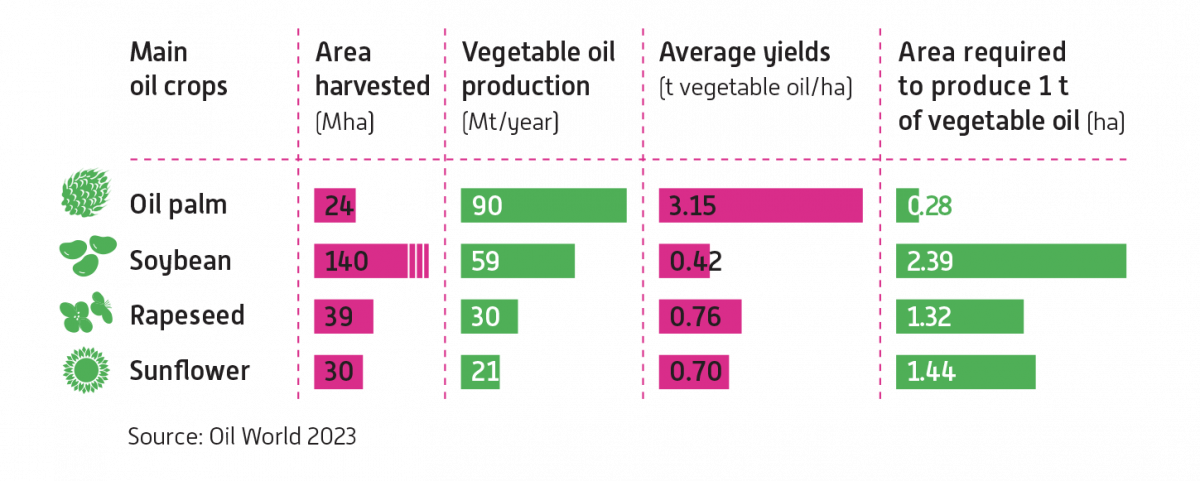

Palm oil has a bad reputation, and for good reason. Vast expanses of monoculture plantations, with oceans of palms, have resulted in deforestation and ecosystem degradation. However, palm plantations are actually more land-efficient than other oilseed crops. It takes an average of 0.28 hectares of oil palm to produce one tonne of vegetable fat, compared to 2.39 hectares for soybean and 1.32 for rapeseed.

In Indonesia, the development of oil palm cultivation over the past 40 years has been one of the leading causes of deforestation. But this activity has also driven economic growth in rural areas. For many families, palm oil production has enabled them to buy land, which they will be able to keep for several generations.

Today, most of these palms are too old to be exploited. To help smallholder farmers to replant, scientists are assessing the impact of different agroecological practices and of cooperation between farms. The goal is to develop economically viable replanting strategies that preserve soil health for several more crop cycles, thus avoiding a new phase of deforestation.

Replanting: a critical period for smallholder farmers

In Sumatra, Indonesia, the majority of oil palm plantations are more than 25 years old. The trees, which now stand at between 20 and 30 metres high, are becoming too tall for harvesting. If they wish to continue producing, smallholders must cut them down and replant. This is a critical period, lasting up to five years, during which these small farms of just a few hectares have no income. Crop diversification is clearly a solution to avoid such income gaps.

Turinah, a PhD student at SupAgro Montpellier, and Suzelle Verant, an agronomist at CIRAD, are working with smallholders on the island of Sumatra, in an area covering 5200 hectares. The two researchers, in cooperation with the University of Jambi and the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture, are proposing viable and resilient replanting methods. “The primary goal is to preserve the social gains of smallholders”, says Turinah. “The risk during replanting is that land will be abandoned and deforestation will occur elsewhere, where trees are easy to cut and soils are untouched by agriculture and therefore still highly fertile. This would mean starting from scratch for these farmers, after having spent years paying off loans on their lands”.

Strategies tailored to different needs

The first stage, which entails removing the old palms, can be carried out individually or collectively. Some farmers’ organizations succeed in pooling financial resources to hire large machinery, thereby reducing the cost of felling. In cases where felling must be done manually, some smallholders first poison their trees. Every felling strategy has its own constraints and benefits. The scientists study farms that have already launched this process and share their findings with plantations that are still in the decision-making phase.

The smallholders then test different agroecological practices for their new crop cycle. “The use of compost helps to protect soils after trees are felled”, says Suzelle Verant. “Planting maize, groundnut, cassava or banana in the first few years provides alternative income sources. We are working to develop a whole range of solutions that each farmer can subsequently adapt to their own farm”.

Planting for the future: the environmental challenge

For farmers, but also for the territory, anticipation is crucial. The palms planted today will be there for the next 25 years. The quality of the varieties used, cultivation methods, and soil condition are assets that these families will pass on to their children. While short-term economic constraints are a priority to sustain their activity, farmers are aware of the ecological impacts of starting another monoculture cycle.

“Today, deforestation has almost ended in Sumatra and smallholders are very aware of regulations, especially for sales to the European Union”, says Turinah. “Most farms avoid using too much chemical fertilizer and have RSPO certification to prove that they follow sustainable development processes for palm oil”.

The Indonesian researcher has been working with producers for more than five years. She hopes to see the development of a wide range of agroecological practices tailored to each farm that will continue to evolve over future generations. “Farmers are trained and can seek support from local NGOs”, says Turinah. “The government also offers financial assistance of 30 million rupiahs per hectare for replanting, provided this is not done in a forest area”.

“If replanting is done properly, we can avoid any further deforestation”, adds Suzelle Verant. “This is a huge challenge for Indonesian agriculture. Research efforts are insufficient, especially to provide small producers with as much agronomic and organizational information and support as possible”.

Reconciling biodiversity and oil palm cultivation

Palm oil is often criticised due to the huge ecological impacts of monoculture palm plantations. However, the plant itself is quite interesting in many ways, for both its productivity and the excellent nutritional quality of unrefined red palm oil.

At CIRAD, several research projects are aiming to develop alternatives to monoculture and bring biodiversity back to palm plantations. This means first diversifying the plants grown in a given plot, for example through agroforestry. This is the goal of the TRAILS project in Malaysia, which combines palms with other plants endemic to Borneo, thereby encouraging the recolonization of landscapes by wildlife. In Mexico, agroforestry systems help to avoid excessive landscape fragmentation and maintain corridors for small wildlife species.