Results & impact 28 October 2025

- Home

- CIRAD news

- News

- Glyphosate is bad for biodiversity

Glyphosate reduces soil biodiversity and the proportion of native soil fauna species

_C.Chabrier.JPG)

Bananeraie de Rivière Lézarde (St Joseph, Martinique) © C. Chabrier

Glyphosate is the world's most widely used herbicide. It is also a word that instantly triggers impassioned debate. It is used in farming to kill weeds and limit their adverse effects on crops. However, the scientific jury is still out as regards its effects on humans and the environment. In terms of policy, the recent renewal of its authorization by the EU has fanned the flames.

Glyphosate's impact on biodiversity is difficult to study in situ

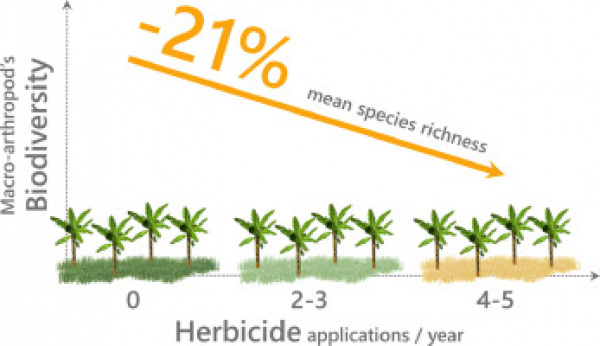

There is a lot of talk about glyphosate's effects on health, but its impact on ecosystems and biodiversity has not been widely studied. However, they may be worrying: our recent study in Martinique showed a 21% reduction in biodiversity on average in banana plots treated regularly with glyphosate.

Martinique is ideal for studying the consequences of glyphosate for biodiversity, since its humid tropical climate fosters seed development in plots and many farmers use glyphosate as a result. However, studying the effects of glyphosate in situ is still very complicated, since numerous farming practices and environmental parameters may vary simultaneously.

Nevertheless, it is crucial not to settle for laboratory research and to conduct field studies under actual operating conditions, to understand those impacts better. This is because the herbicide application method, whether spraying or localized applications, and the use of additives, may result in different effects on the fauna.

Similarly, the degree to which invertebrates are exposed to herbicides, for instance, is influenced by a range of factors that cannot always be studied in the laboratory, such as the species' behaviour or life cycle.

A 21% reduction

To be able to conduct our study despite the above, we interviewed a large number of farmers in order to select fields in which farming practices were absolutely identical, except for the farmers' weed control methods. This allowed us to study the effect of glyphosate – easily the herbicide most used in Martinique – on farms that no longer used herbicides in general (replaced by using a brush cutter), that used them less frequently than before (two or three application rounds/year) or that still used them frequently (four or five rounds/year).

We collected more than 6000 invertebrates of 105 species in those plots, and found that glyphosate had a significant influence on soil invertebrates in tropical environments: it reduced mean species richness by up to 21%. In other words, plots treated with glyphosate contained fewer species on average.

Glyphosate also affected abundance (the total number of individuals) in every link of the soil fauna food chain. The most affected trophic groups were predators and decomposers (invertebrates that eat plant waste): their numbers fell by 54% and 23% respectively in the plots treated most often.

A gradual effect on biodiversity

How can we explain this? The mechanisms involved are difficult to establish in situ, as a number of interacting parameters may be involved, but as things stand, the most likely hypothesis is that glyphosate acts indirectly, through a cascading effect: by destroying the plant cover, it destroys the soil fauna's habitat and a major share of its food supply, thus affecting the entire trophic network.

In addition to demonstrating a simple negative effect, our results also showed that glyphosate had a gradual effect on biodiversity, depending on treatment frequency. In plots given two or three herbicide treatments per year, the reduction was 16%, while the figure was 21% for plots given four or five treatments per year. The less glyphosate is used, therefore, the less biodiversity is affected. Reducing its use is therefore a first step for farmers towards preserving biodiversity within crop plots.

Why preserve soil biodiversity in fields?

It is vital that we preserve biodiversity in agricultural plots, for two main reasons. The argument most often heard is that soil biodiversity is useful by virtue of the ecosystem services it renders, or of its utilitarian value. Predator biodiversity, for instance, can play a major role in regulating pests and thus helps to reduce the need for insecticides. Decomposers (for example millipedes and woodlice) also help substantially to break down leaf litter. Increasing decomposer numbers in agro-ecosystems would therefore boost nutrient recycling and plant growth. Other species such as ants also improve water infiltration by modifying the soil structure as they move around and build nests, a process known as "bioturbation".

Conserving biodiversity for its own sake (for its intrinsic value) is the other argument. For instance, the Caribbean, which includes Martinique, is a biodiversity hotspot with a large number of endemic species that often only live on one island, and if they die out on that small area, that often makes them globally extinct. However, changing land use generally means converting natural areas to agriculture, particularly in the tropics, which threatens the survival of those species.

Glyphosate affects native species more severely

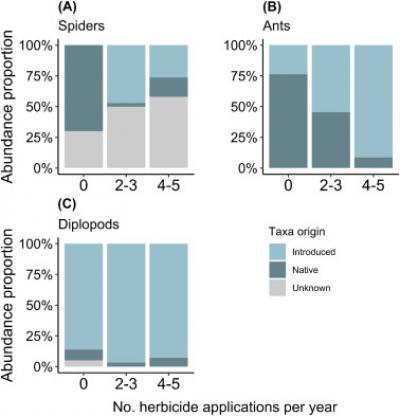

Our study also showed that using glyphosate tends to favour exotic soil invertebrate species to the detriment of native ones. Little is known about the mechanisms involved, but the probable culprit is a number of complex indirect effects. The assumption is that glyphosate acts in a similar way on the entire soil fauna, but that exotic species are able to recolonize disturbed habitats more quickly. As a result, in environments disturbed by frequent herbicide use, the proportion of exotic species tends to increase.

This result is important in terms of conserving biodiversity, since along with lane use changes, invasive exotic species are one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss on a global scale. The fact that glyphosate favours exotic species to the detriment of native ones had never previously been demonstrated in animals. Glyphosate is even sometimes used to control invasive exotic plants in natural environments, which could thus prove counterproductive and have repercussions for other organisms such as soil fauna.

What are the alternatives to glyphosate?

On the whole, our results show that in conditions where glyphosate is used frequently and is an integral part of the cropping system, it is difficult for agricultural environments to help conserve soil invertebrate biodiversity. However, in view of the rate at which natural environments are currently being converted to agriculture, particularly in tropical zones, it is important to be able to preserve biodiversity in fields if we are to prevent a 6th mass extinction. So what can we do?

Applying herbicides less frequently is an interesting suggestion, but the main current challenge for farming is to learn how to grow crops without destroying other plants. When making that transition, however, it is important to be wary of possible alternatives that could be worse than glyphosate, for instance more frequent ploughing, which could be harmful for soil biodiversity.

However, various solutions exist or are under study. Technology-based solutions using suitable mowing equipment or robots are showing promise. Introducing herbivores into plots could be another solution. For instance, one possibility that CIRAD is already testing in banana plantations in Guadeloupe is using sheep to manage weed growth. This solution could also have other advantages, notably in terms of crop fertilization.