Science at work 16 December 2025

- Home

- Press area

- Press releases

- invasion pests Africa

Locust invasion: stepping up research and training to ensure ongoing prevention

Adult gregarious desert locust © CIRAD

"Tens of thousands of hectares of agricultural land and rangelands have been devastated in Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya. More than 20 million people are facing food insecurity. Further east, over the past two years, locusts have swarmed through several countries in the Arabian Peninsula, Pakistan, Iran and India, where the critical situation in Rajasthan is currently headline news. They are also likely to spread westwards, with the prevailing winds, and eastern Uganda and South Sudan are already affected. Chad and subsequently West and North Africa could be hit in the coming months."

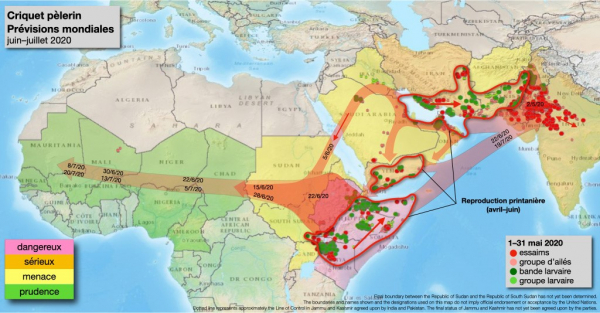

Forecast map for the spread of desert locusts over the period up to July 2020, supplied by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Locust Watch, 4 June 2020. As long ago as early 2019, small desert locust swarms formed and then spread throughout the Arabian Peninsula, as far as Iran, Pakistan and then India.

CIRAD researchers Antoine Foucart, Pierre-Emmanuel Gay and Cyril Piou start their article with an alarming observation: the current desert locust invasion in East Africa is the worst for decades and is costing unprecedented amounts of money. Since the 1960s, locust control and preventive management had slashed the number of attacks, so what triggered the new invasion?

In addition to favourable environmental conditions – abundant food supplies due to heavy rains along the coast of Yemen and Oman in October 2018 – the authors point the finger at a lack of preventive management in several East African countries. They recommend stepping up training operations and investing in quality preventive forecasting tools.

As they point out, "preventive management is facilitated by the accumulation, over the years, of field prospectors' expe rience, knowledge of insect ecology built up through scientific research, and maps of the zones that foster invasions, drawn up using satellite images".

This long-term dynamics is proof of the importance of ongoing field surveillance, international cooperation between the countries concerned, and scientific research to know more about the pest and develop more environmentally friendly control methods.

Preventive management, to avoid the formation of swarms Desert locusts are one of the few locust species capable of changing their behaviour depending on the environmental conditions and their population density. They are generally solitary, but may swarm in the event of favourable climatic conditions. In other words, they become gregarious. "If the population density is high enough, gregarious individuals initiate […] mass movements. Young insects form hopper bands, which are like vast flying carpets of several thousand wingless individuals that can cover several hundred metres a day. Once adult, they form swarms of winged individuals that can cover long distances (up to 150 km a day) on the back of the prevailing winds and rain fronts, such as the seasonal displacement of the intertropical front, searching for fresh food. Swarms can exceed several dozen square kilometres in size and comprise billions of individuals. They wipe out any form of vegetation, including food crops, in their path." The researchers see preventing locusts switching from the solitary to the gregarious phase as the best management solution, since once they have swarmed, it is much more difficult to control invasions. |

Read the article in Passion Entomologie by Antoine Foucart, Pierre-Emmanuel Gay and Cyril Piou, published on 8 June 2020 (in French)