Call to action 25 November 2025

- Home

- CIRAD news

- News

- The climate data paradox

The paradox of climate data in West Africa: growing urgency coupled with diminishing accessibility

Senegalese farmer walking through a field © R. Belmin, CIRAD

In 2022, a prolonged drought devastated maize crops in northern Burkina Faso, leaving two million people without sufficient food resources. This dramatic situation could have been better anticipated and its impacts could have been mitigated with the collection and equitable sharing of specific data: that of agrometeorology, the science that studies the effects of meteorological, climatological and hydrological factors on crops.

Although it is too late to prevent the 2022 drought, protecting people from future droughts remains an urgent priority, especially in Africa, a continent where climate change poses a serious threat to rainfed agriculture, its main agricultural and economic activity.

To anticipate these climate risks, it is essential to have access to reliable meteorological data, which is crucial for ensuring sustainable and resilient agricultural practices. Yet in West Africa, the accessibility and reliability of this data are increasingly threatened and face unprecedented diplomatic, economic and security challenges.

The evolution of the data landscape and emerging paradoxes

To explain how this situation emerged, it is important to first understand the purpose of agrometeorological data and how it began to be collected.

Agrometeorological data, which mainly includes information on rainfall, temperatures and humidity, along with sunlight and wind, is essential for agricultural planning. In West Africa, where the predominant system is rainfed family farming, which is vulnerable to climate variability and change, this data underpins numerous crop monitoring indicators.

It can be used, for example, to define optimal planting dates to minimize the risks of “false starts” (when planting occurs too far ahead of the rainy season, leading to loss of seedlings), to monitor whether crop water requirements are being met, or to anticipate the emergence of diseases and pests. It can also be used to predict crop yields and to prepare for extreme weather events. In short, this data contributes to anticipating risks, whether these are attributable to the natural variability of weather conditions or to climate change, both of which are significant challenges in the region.

How has work been organized around agrometeorological data?

Since the 1970s, CIRAD has been developing tools and methods related to agrometeorological data. Its work has laid the foundations for mathematical models such as BIP, DHC and SARRA, which are used to produce maps estimating water stress and its impact on agricultural yields according to climate conditions. Cooperation between CIRAD and regional organizations such as the AGRHYMET centre (a CILSS – Inter-State Committee for Drought Control – agency created in response to the major droughts of the 1970s) has been crucial for the development of these tools. As a regional climate centre, AGRHYMET is the armed wing of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in terms of monitoring and managing agricultural risks. It implements these tools through early warning systems and contributes to capacity building for national meteorological services.

In recent years, the agrometeorological data landscape has evolved significantly due to the use of new techniques, which have enabled a welcome increase in the amount of data available.

In particular, advances in remote sensing have revolutionized the collection and analysis of new types of data. This set of techniques is used, among other things, to measure and quantify daily rainfall, surface temperature or vegetation status using sensors mounted on satellites, weather radars or aircraft. By integrating this data into global climate models (see, for example, AgERA5, provided by the EU Copernicus Earth observation programme), it is possible to access estimates of meteorological variables at any point on Earth, even in inaccessible areas or those that are poorly equipped with ground measurement instruments, at a scale of a few tens of kilometres.

However, ground reference points remain absolutely necessary to calibrate, validate and develop these estimation and forecasting methods, as well as to establish new approaches (such as estimating rainfall by analysing disruptions to mobile phone networks). Indeed, these reference points can be used to correct values derived from remote sensing, since these observations may be distorted by cloud cover on the day, a sandstorm, instrument drift, etc. This reduces the accuracy of meteorological and climate models, which, in any case, tend to be initially less reliable in Africa.

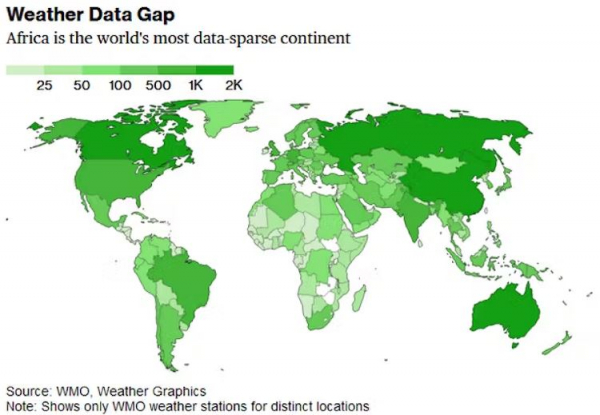

Historically, the collection of these reference points was carried out by the national meteorological services through their networks of stations, which are unevenly distributed across the region. However, the continent faces significant challenges in terms of meteorological infrastructure. With an average of one station for every 26 000 square kilometres, or around eight times fewer than the minimum level recommended by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), Africa has the lowest density of meteorological stations in the world. Another example is that the United States and the European Union, with a combined population of 1.1 billion people, have 636 weather radar stations, whereas Africa, with a similar population of 1.2 billion people, has just 37.

Global distribution of the number of synoptic weather stations monitored by the WMO. Article “Africa Is the Continent Without Climate Data”, Bloomberg, August 4, 2021

The paradox of selling data

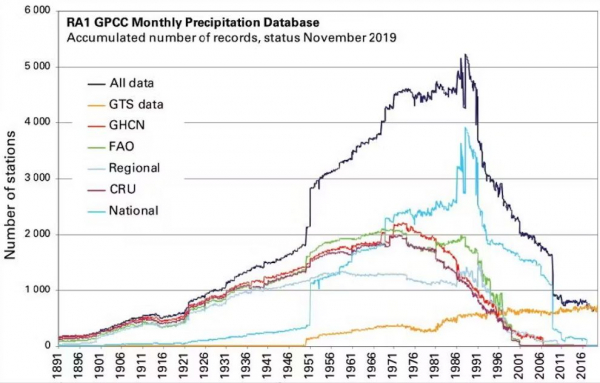

Furthermore, despite the urgent need for reliable data for agriculture, there has been a rapid decline in the number of meteorological stations in Africa over the past 40 years. Several academic studies analyse in detail the factors behind this decline, including underfunding of national meteorological services, a lack of personnel and infrastructure, and the degradation of existing infrastructure.

This has created a paradox: although the lack of data directly affects meteorological services, they have resorted to selling their data to ensure their own survival. While this provides short-term financial relief, it creates long-term obstacles to data access, precisely when this data is more essential than ever for decision-making, research and public use.

Evolution over time of the number of rainfall stations in Africa – total number in black, distribution by networks in colours. “State of the Climate in Africa 2019” report, WMO

This paradox is further complicated by security issues, which profoundly affect meteorologists both in the field and in the office. While the problem of data applies to a large part of the African continent, West Africa also faces political instability, conflicts and terrorist activities, which disrupt data collection and management.

Moreover, although AGRHYMETis responsible for pooling and safeguarding national meteorological data, in recent years some countries have simply ceased their transfers. Consequently, the sharing of this data has become a source of diplomatic tensions between countries in the region, but also with the countries of the North, which use this data for their development research activities.

These challenges strain the resources of regional organizations like AGRHYMET, CILSS and ACMAD (the African Center of Meteorological Applications for Development), limiting their effectiveness. The declining influence of ECOWAS (the Economic Community of West African States), due to internal divisions and external pressures, is exacerbating the problem. Institutions that depend on ECOWAS for support and coordination are losing the institutional framework that facilitated this data sharing.

This evolution in the meteorological landscape has enabled the emergence of new private actors such as the TAHMO (Trans-African Hydro-Meteorological Observatory) initiative, a company formed by Delft University of Technology (Netherlands) and Oregon State University (United States). TAHMO is attempting to address this paradox by developing a complementary observation network based on a hybrid economic model:

- The stations are financed and deployed by research programmes and development initiatives, which retain ownership of the data.

- Data from the stations is transmitted to the network and provided free of charge to national meteorological services as well as to researchers who request it.

- Data from the network is sold to private initiatives.

However, this paradox highlights a critical issue: the data needed to improve agricultural resilience and food security is becoming increasingly inaccessible at a time when it is needed most. Indeed, after 20 years of progress in food security across Sub-Saharan Africa, the indicators are now declining.

The way forward: a call for open data

To address these challenges, it is essential to recognize meteorological data as a public good. Ensuring open access to this data is crucial for accurate modelling, forecasting and decision-making in agriculture, conducted by researchers or companies from the countries of the north, and especially by researchers and entrepreneurs from the countries of the South.

This issue has been fully understood by actors such as Météo-France, which opened all of its data in late 2023, and by the World Bank, which provides open access to the results of its integrated survey on agriculture, ensuring linkages between agrometeorological signals and observations of farming practices. The question of safeguarding and digitizing archival documents and providing access to historical databases is also critical. However, this raises concerns when large datasets are held by private companies, a problem we encountered with our dataset on rainfall in northern Cameroon, which is largely based on data from the national cotton company.

How can data be made more accessible?

Several measures can be taken to move in this direction:

- Innovative funding mechanisms: Developing sustainable financing models for national meteorological services, including ambitious national strategies, international aid and public-private partnerships (for example, the Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Agricole du Sénégal [CNAAS – Senegal National Agricultural Insurance Fund] finances the rain gauge network as part of an index insurance service).

- International cooperation: Strengthening international collaboration to support regional initiatives for data collection and sharing, with organizations like the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) playing a crucial role.

- Capacity building: Investing in training, infrastructure development and technical support to improve the capacities of national meteorological services.

- Political advocacy: Promoting policies that recognize and protect the public nature of meteorological data, by engaging governments, regional bodies and international organizations.

In conclusion, given the lack of investment in costly meteorological observation infrastructures such as radars (which are almost non-existent in Africa) and the need to sustain existing stations, the best short-term solutions to improve resilience to agro-meteorological shocks are ensuring the maintenance and upkeep of the current observation network and promoting open access to data.

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation on 14 August 2024.