Expert view 5 March 2026

- Home

- CIRAD news

- News

- Origin of Covid-19 virus

Origin of the Covid-19 virus: the mink farm theory

On January 14, a team of international experts commissioned by the World Health Organization arrived in China for a three-week mission with the aim of visiting Wuhan to meet Chinese scientists and help to pinpoint the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus responsible for the pandemic. The mission has received criticism, and some scientists are calling for an independent inquiry into the origins of the pandemic in China.

The Covid-19 crisis has shown that past plans aimed at preparing for pandemics were not sufficient. To prevent future pandemics, strategies must be in place before viruses even begin to develop in humans – in other words, within the animal kingdom and at the animal-human interface.

It is therefore essential to identify the origin, the evolutionary processes and the initial chains of transmission that led to the current pandemic. This must also be seen in the light of the determinants of that emergence.

It is thought that the coronaviruses that have emerged in recent years (SARS, MERS-CoV) circulate in bats and were transmitted to humans by intermediate host animals. These diseases are known as zoonoses. The role of a domestic or wild animal is often observed in the case of zoonotic coronaviruses – the camel for MERS-CoV and the masked palm civet for SARS, although doubts persist about whether it is indeed this small mammal that is involved, rather than other wild animals raised in China.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines a zoonosis as a disease or infection naturally transmissible from vertebrates to humans – and vice versa. The current pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has been class as a zoonosis, but no animal reservoir or intermediate host has yet been formally identified. This classification thus seems premature to some authors who identify this disease as an “emerging infectious disease (EID) probably of animal origin”.

The first patients officially declared to have Covid-19 in China were probably exposed to the virus at a seafood market in Wuhan. However, while some of the swab samples taken from surfaces and cages in the market tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, no virus has been isolated directly from animals and no animal reservoir has yet been identified. Nevertheless, the hypothesis (animal lead) is that the coronavirus evolved from an ancestral virus found in bats, via an as-yet unidentified mammal.

Many different species can be infected with SARS-CoV-2

The virus has been detected in animals exposed to infected humans – domestic cats, dogs and ferrets, captive lions and tigers, farmed mink – as well as gorillas, indicating possible transmission from humans to animals (reverse zoonosis) and the receptivity and susceptibility of carnivores, in particular mustelids.

One of the recent hypotheses as to the intermediate host that may have allowed the evolution of an ancestral virus into SARS-CoV-2 (the Covid-19 virus) concerns mink that are raised in China for their fur. In China, the rearing of wild animals for food, therapeutic purposes and fur has grown considerably over time, and is now the livelihood of millions of people.

Fur production has grown rapidly in China since the 1990s and most farms were built recently, with little technical or veterinary supervision. Its economic importance is now considerable, with fur farming employing around 7 million people. The main species farmed in China for fur are mink, fox and raccoon dog, with annual production estimated at, respectively, 21, 17 and 12 million animals slaughtered in 2018. The mink-farming industry is largely unstructured. According to 2016 estimates, almost half of farms are small-scale family businesses with fewer than 1,000 mink, while the remainder are medium-sized farms as well as a minority of integrated factory farms with between 10,000 and 52,000 animals.

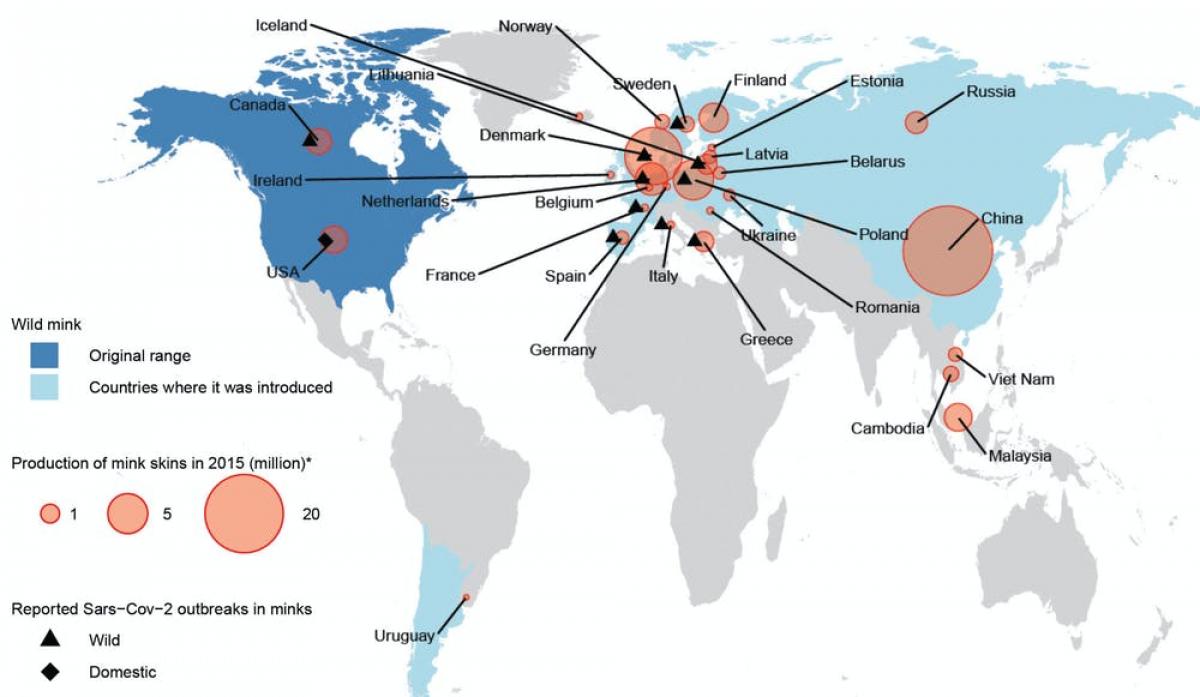

American mink distribution areas. The species was introduced into Eurasia for the production of fur, but many individuals escape from farms or are released into the wild). The cases of Covid-19 (OIE) declared on farms correspond to transmission from humans to animals © CIRAD

The receptivity and susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 of mustelids, including the American mink (Neovison vison ), documented in the context of transmission from humans carrying the virus, and taking into account other genetic, economic, ecological and epidemiological elements, direct suspicions toward these species. Moreover, work on cell receptors (ACE2) has shown that many species could be receptive to SARS-CoV-2, particularly primates or carnivores. However, the authors of this study stress the importance of avoiding over-interpreting the predictions put forward and point out that experimental and observational data in the field are required.

Infectious diseases are on the rise

Infectious diseases have emerged with increasing frequency since the mid-20th century, and they’re more probable in geographical zones marked by an increase in the pressure exerted by man on natural areas, by great animal biodiversity, by the transformation of natural spaces into agricultural land, and by the hunting and capture of wild animals. In developing countries, more than cultural factors, it is often the combination of economic insecurity and low agricultural productivity that lead poor rural communities to harvest wild animals or their products, to use as food (bushmeat), commercial products, or agricultural inputs. This is the case with bat guano, which is used as a fertilizer in Southeast Asia.

Domestic and wild animal production promotes the spread and increased virulence of emerging pathogens, due among other things to the transport of animals over long distances, and to the storage of high densities of animals with shirt life cycles and often with limited attention to biosecurity. In addition, breeders follow cost-cutting strategies that can hinder the early detection and control of emerging diseases: animals showing symptoms of disease are quickly sold. The lack of transparency in animal supply chains often allows sick animals to be marketed along with others that are healthy.

These elements provide a better understanding of how mink farms could have acted as an intermediary between bats and humans in the case of SARS-CoV-2. This phenomenon was observed for avian influenza, with the virus being introduced through contact with asymptomatic wild reservoirs (palmipeds), followed by the amplification of the disease in intensive, high-density farms and the eventual production of mutant viral strains that are virulent for the initial wild reservoir species.

Economic fears

The acceptability of health surveillance systems also comes up against economic logic, with farmers fearing the impact of announcements of disease outbreaks on market prices and their ability to export. Conversely, the mass slaughter of farm animals often pushes up prices, as seen in China after Denmark’s slaughter of farmed mink, and paradoxically increases the profits of farmers not affected by the control measures.

In addition to ecological factors, economic factors are frequently encountered in low- and middle-income countries: economic insecurity of poor rural farmers, rapid growth in exploitation of wild and farmed species to meet growing demand for animal products, and a lack of transparency in agricultural sectors.

Studies are necessary in a One Health perspective. This would involve looking for viruses and antibodies in samples collected and stored before the Covid-19 pandemic through various studies in animals and humans; analyzing samples from mink farms, but also raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides ) and foxes (Vulpes spp.) for coronavirus and typing any viruses found; conducting epidemiological studies based on serologies specific to a response to SARS-CoV-2 on those farms, on animals and exposed human populations; and analyzing and modeling the links between bats and wildlife farms and between these farms and human populations.

Fur breeders should be surveyed on how they manage infectious disease cases, since their response (attempted treatment, selective sale of sick animals, etc.) can influence the risk of emergence in humans. Studies are required relating to the organization of the fur industry and its links with wild animal or wild animal product supply chains.

Field projects are focusing on studying the risks of the emergence of coronaviruses from wildlife and the wildlife trade. The ZooCoV project, which began in Cambodia and associates CIRAD, the Institut Pasteur in Cambodia, IRD and the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), should boost our knowledge of wild-meat supply chains and thus help prevent and control the health risks associated with such practices.

Prevention is the key

On a more global scale, it is necessary to prevent the risks of zoonotic emergencies and pandemics. To this end, the PREZODE initiative, announced during the January 2021 “One Planet Summit”, will build on and strengthen existing cooperation with the world regions most exposed to the risk of zoonotic disease emergence. PREZODE will support the integration and strengthening of human, animal and environmental health networks, in line with the One Health approach, in order to better assess and detect threats of zoonotic disease emergence and develop prevention operations with the entire range of stakeholders so as to protect people, the planet and socio-ecosystems and thus reduce pandemic risks.

Following the China mission, the team of experts appointed by the WHO concluded that the hypothesis of the virus having escaped from a laboratory was highly unlikely. They felt that the theory of an intermediate host between bats and humans was the most likely, and that the possible role in the spread and amplification of the virus of frozen foods and of markets like the one in Wuhan should also be considered. However, fundamental questions remain: when, where and how did SARS-CoV-2 first infect humans?

In this context, it is worth noting that a recent FAO-OIE-WHO report also observed the existence of fur farms in Southeast Asia. Moreover, recent studies in the region identified a betacoronavirus similar to SARS-CoV-2 in bats ( Rhinolophus shameli ) captured and sampled in Cambodia in 2010. Another betacoronavirus, also similar to SARS-CoV-2, was also isolated from a different bat species (Rhinilophus cornutus ), this time in Japan in 2013.

This information prompts an expansion of the geographical zone within which spillover may have occurred via domestic animals or wild species, either farmed or hunted and consumed, including bats. Indeed, in some parts of Southeast Asia, wild animal meat is commonly traded and consumed. In Cambodia in particular, pangolins, civets and raccoon dogs, which are particularly susceptible to infection by SARS-CoV-2, are some of the species concerned.

As stressed by the WHO experts, this means that inter-species transmission may have been possible south of Wuhan, and potentially outside China, followed by amplification through Wuhan’s live-animal markets, which would therefore be a secondary cluster of the epidemic rather than the original focus.