Science at work 9 March 2026

- Home

- CIRAD news

- News

- Diagnoses of food systems

Diagnoses and debates, for more sustainable food systems

Rice seller at Moramanga market, Madagascar © CIRAD, M. Barale

There will be no sustainable development without profound changes in food systems. This belief is shared by CIRAD and its partners, plus the United Nations, which is organizing a Food Systems Summit this September.

The FSA (Food System Assessment) project was initiated by the European Union, FAO and CIRAD, to conduct national food system diagnoses. The conclusions of their assessments will fuel dialogue between policymakers and players directly involved in food systems. They may also contribute to or supplement the runup to the United Nations Food Systems Summit.

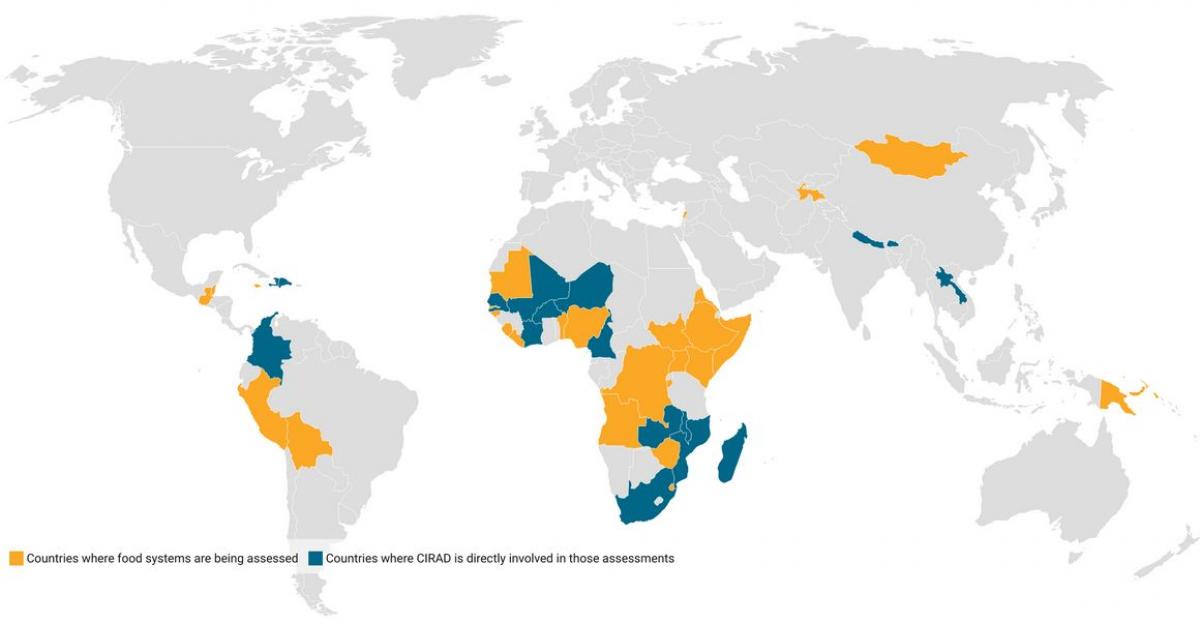

In all, 47 countries have agreed to an assessment of their food systems.

Food systems are linked to most of the sustainable development goals

Soaring population growth, changing diets, environmental degradation, unstable markets, and now pandemics... there have never been so many threats hanging over food systems.

Those systems are a major economic sector in every country worldwide. However, the wealth they generate is often unfairly distributed, generally to the detriment of small-scale producers and traders. Moreover, there is often lingering malnutrition – populations suffering from both micronutrient deficiencies and obesity –, resulting in diet-related chronic diseases.

Lastly, food systems account for almost a third of global greenhouse gas emissions, consume vast quantities of natural resources, and are contributing to critical biodiversity losses.

To engineer future changes, it is vital to understand how those systems function on a national and sub-national level.

"Diagnosing food system performance – and the main risks those systems face – is crucial if we want to work together to design the future, build alternatives and identify possible compromises, to set food systems on a more sustainable path", says CIRAD's Ninon Sirdey, and economist and co-coordinator of the project.

A diagnosis method built on CIRAD's expertise

CIRAD built the methodology being used for the diagnoses, which are being conducted in collaboration with FAO. It alternates qualitative and quantitative data analyses (current indicators and historical trends drawn from international databases, national statistics, reports, the scientific literature and thematic maps), stakeholder surveys, and multi-player workshops.

The diagnosis made takes account of the differences between countries. It serves to determine the opportunities available and the main challenges facing food systems, and to pinpoint levers capable of triggering positive changes in food systems.

Each study involves a team of national and international experts trained in the methodology by three researchers from CIRAD.

National policymakers are involved in every assessment. They take part in workshops and follow updates on the assessments and synopses.

Initial results in Burkina Faso and Madagascar

Providing the entire population with healthy food is one of the main functions of food systems. In Burkina Faso and Madagascar, this is a vital issue, since the food and nutrition situation remains critical for a major part of the population.

However, the diagnoses conducted in these two pilot countries have shown that food systems do not merely supply food:

- They play a major role in the economy (42% of GDP in Burkina Faso and 37% in Madagascar) and employment (56% and 68% respectively), and a determining role in ejnuring food security.

- They are still fragile and face future risks if current trends continue. For instance, the steady land degradation in Burkina Faso (the result of farming practices and of the agro-climatic conditions in the Sahel) is a threat to future production capacity. Insecurity and a lack of infrastructures are hampering the development of vast areas in Madagascar, while land pressure is a threat to the viability of most very small farms.

Issues specific to each territory

Situations vary substantially from one region to another. For instance, the challenges facing the southern half of Madagascar, which has suffered recurrent droughts for several years, along with very significant insecurity, are very different from those in the central highlands, with their very diverse production systems driven by the main centres of consumption, but where family farming is hampered by the very small areas available.

Four vital levers for efficient food systems

Lastly, the project has pinpointed specific levers for each country and territory, and discussed them with various players in the public-and private sectors and civil society. In addition to providing infrastructures and basic services, which are seen as vital for efficient food systems, the other levers pinpointed concern:

- restoring natural resources (notably soils), as a cornerstone of sustainable food systems in the medium and long term;

- developing producer support services, to foster a switch to sustainable intensification practices;

- supporting and organizing postharvest players and operations (aggregation, processing), to shift the balance of power in favour of small-scale producers and boost added value at territory level.

Contribution to the runup to the Food Systems Summit

The results of the diagnoses will contribute to or supplement the runup to the Summit, by giving the countries involved a substantiated picture of their current food systems, the main challenges facing them, and the potential levers for change.

Food systems encompass all the stakeholders and activities involved in the production, collection, transport, processing, distribution and consumption of foodstuffs resulting from agriculture, silviculture and fishing. They include the inputs used and management of the waste generated by each activity.

Food system stakeholders and activities are influenced by a range of independent social, political, cultural technological, economic and environmental factors. At national level, some drivers (eg political factors) can be controlled, whereas others are imposed upon food systems (for instance climate change).

Food systems act on four main levels: food security, nutrition and health; socioeconomics; territorial balance and equity; and environment.

Their effects and drivers are linked by feedback loops and synergies. The system as a whole therefore involves a range of players from the public and private sectors and civil society, and requires several levels of governance.