Call to action 25 November 2025

- Home

- CIRAD news

- News

- One Health: State-science-society dialogue is vital

Health is everyone's business. State-science-society dialogue is vital for One Health approaches

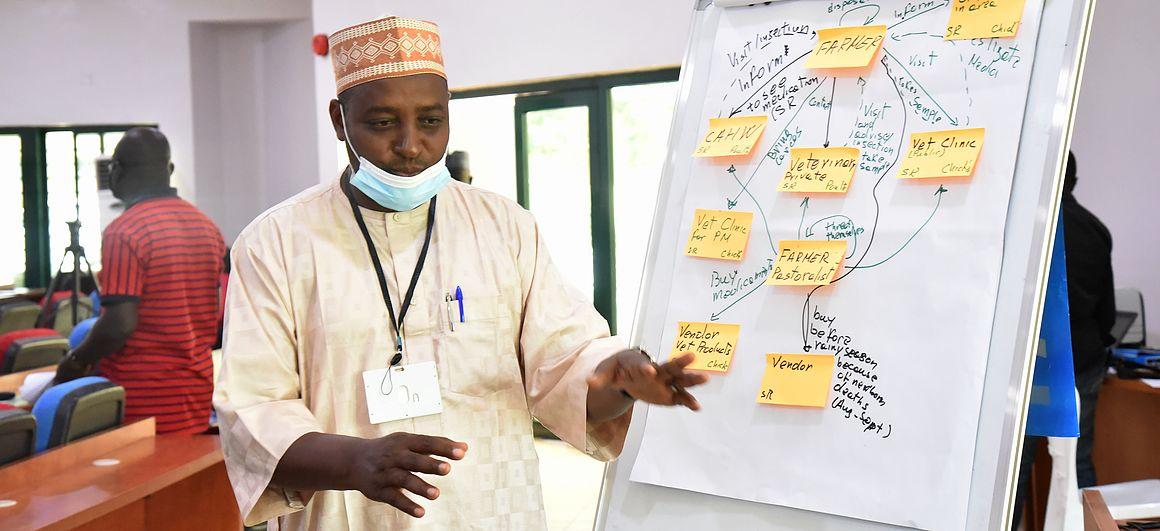

Multi-stakeholder workshop held as part of the Lidiski One Health programme © Ikore

The Covid-19 pandemic has served to raise awareness of the impact global change has on disease emergence and spread and their adverse health and socioeconomic consequences. However, while the One Health concept is universally recognized as a way of preventing and controlling pandemics, concrete action is still in short supply. How can such approaches be put into practice? This was the question addressed by a number of decision makers, field players, institutional representatives and scientists, including CIRAD researchers, at a seminar in March 2021. The thread running through a recent publication summarizing their discussions was the need for State-science-society dialogue. "The first stage in any One Health project is to break down any sectoral barriers and ensure that different disciplines and scales, from a local, field to a national level, work together", says Aurélie Binot, an anthropologist and agronomist at CIRAD.

Participatory science, an asset for health monitoring systems

The whole range of stakeholders, on every level, must work together to build One Health operations. Since citizens are at the heart of the processes by which health risks emerge - and are both the main victims and/or sometimes the cause of those processes -, it is vital that they participate, "to guarantee that health strategies are both relevant and implemented effectively", Marisa Peyre, an epidemiologist at CIRAD, points out. Indeed, "taking into account the needs, constraints and views of people in the front line serves to bring them on board, since they know any standards drafted are based on their real-life experiences", her colleague Marie-Marie Olive adds. In Guinea, CIRAD is working on the practical implementation of community monitoring systems, via the EBO-Sursy project.

Building health monitoring systems specific to different contexts, by means of a bottom-up approach is central to an international initiative, PREZODE – PREventing ZOonotic Disease Emergence, initiated and structured by CIRAD, INRAE and IRD, which is launching its first projects this year. "The ongoing science-society-policy dialogue being spearheaded by PREZODE is crucial to preventing future pandemics", says Marisa Peyre, who is coordinating the initiative for CIRAD.

Role play, transmission frescoes, mapping, forum theatre, and so on... CIRAD is using a range of participatory anticipation and modelling tools to back up an iterative approach it is working to formalize. "For a given zone, we identify the different risk management stakeholders and encourage them to interact in order to draft collective action programmes", Aurélie Binot explains. The Health & Territories project, on which she is working, uses living labs to bring together local research and innovation players to test consultation frameworks and activities aimed at fostering a bespoke agroecological transition in their local area, in line with the health issues identified locally. The BCOMING project is another example, which is using innovative participatory approaches to control infectious disease emergence by means of biodiversity conservation strategies.

Action research in support of public One Health policy

While addressing the needs of those people on the front line is crucial, legislative and political support on a national level is required to enable the necessary reforms. In Southeast Asia, work on African swine fever by CIRAD, the NGO Agronomes et vétérinaires sans frontières and their partners has produced action research results of use to the authorities.

"H5N1 avian influenza, SARS and Ebola primarily concern countries in the global South. As a result, it is those countries that are more aware of integrated approaches and better prepared", says François Roger, a veterinarian and epidemiologist who is CIRAD Regional Director for Southeast Asia. "There is multi-level and multi-stakeholder coordination in Vietnam, where the One Health Partnership associates the Ministries of Health, of Agriculture and of the Environment with research organizations, international bodies and NGOs."

"The Covid-19 pandemic has been something of a wake-up call in Europe", François Roger adds. "We are now more aware of the risks of infectious diseases, which used to be seen as a "southern" issue, while we were more interested in non-contagious and chronic diseases. Antimicrobial resistance, a major issue at the crossroads between health, agriculture and the environment, is a good reason to think about One Health approaches. Intersectoral collaboration in France has given good results.

It was with this in mind that the new French Committee for the monitoring and anticipation of health risks (COVARS), which permanently replaces the Covid-19 Scientific Council, was set up to address infection risks in both humans and animals, along with the risks linked to climate change and air, soil and water pollution. "The new Committee is clearly part of a One Health approach", says Thierry Lefrançois, Director of CIRAD’s Biological Systems department and committee member. The committee, which was set up under the aegis of the Ministries of Health and of Research, works with the Ministries of Agriculture and for Ecological Transition and is made up of scientists, doctors and veterinarians, plus patient and citizen representatives. "The composition of the committee clearly illustrates the need for interaction between decision makers, scientists and players from civil society", Thierry Lefrançois stresses.

Assessing One Health approaches to guarantee their sustainability

"We have to provide proofs-of-concept to show that tackling infectious risks by means of a transdisciplinary, multi-scale approach really works", Marie-Marie Olive says. "Measuring the impact of One Health initiatives is a research field in its own right, and a crucial one."

Over the past 15 years or so, CIRAD has been helping to develop tools to assess cost effectiveness and adapt the approach to specific issues, etc. One example is a vast study currently being conducted by CIRAD and FAO as part of the PREZODE initiative, via a questionnaire distributed in several countries to assess the added value provided by One Health approaches.

Training and alerting societies

In the academic sector, various initial and vocational training courses in One Health are helping to bring together different disciplines and forge links between Faculties of Medicine, Biology and Social Science and veterinary and agricultural colleges. For the first time, the latest edition of Pilly, a French reference work on infectiology, has a chapter on the One Health concept, co-written by CIRAD. It also lists available One Health Masters and MOOCs. "Civil servants should be trained in the need for a holistic approach to health, for instance by means of course modules at the Institut national du service public (INSP, the main training organization for French civil servants), says François Roger, who contributed to the latest Pilly.

More broadly speaking, societies as a whole should be made more aware of the links and interdependencies between health and environment. "Right from school, it is vital that people understand that everything is linked. Just because the different interactions are complex, that doesn't mean that the average citizen is not capable of understanding them", Marie-Marie Olive points out.